Metrics, tracing, and logging

2017 02 21Today I had the good fortune of attending the 2017 Distributed Tracing Summit, with lots of rad folks from orgs like AWS/X-Ray, OpenZipkin, OpenTracing, Instana, Datadog, Librato, and many others I regret that I’m forgetting. At one point the discussion took a turn toward project scope and definitions. Should a tracing system also manage logging? What indeed is logging, when viewed through the different lenses represented in the room? And where do all of the various concrete systems fit in to the picture?

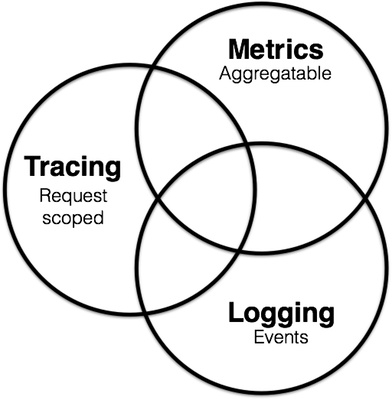

In short, I felt that we were stumbling a little bit around a shared vocabulary. I thought we could probably map out the domain of instrumentation, or observability, as a sort of Venn diagram. Metrics, tracing, and logging are definitely all parts of a broader picture, and can definitely overlap in some circumstances, but I wanted to try and identify the properties of each that were truly distinct. I had a think over a coffee break and came up with this.

I think that the defining characteristic of metrics is that they are aggregatable: they are the atoms that compose into a single logical gauge, counter, or histogram over a span of time. As examples: the current depth of a queue could be modeled as a gauge, whose updates aggregate with last-writer-win semantics; the number of incoming HTTP requests could be modeled as a counter, whose updates aggregate by simple addition; and the observed duration of a request could be modeled into a histogram, whose updates aggregate into time-buckets and yield statistical summaries.

I think that the defining characteristic of logging is that it deals with discrete events. As examples: application debug or error messages emitted via a rotated file descriptor through syslog to Elasticsearch (or OK Log, nudge nudge); audit-trail events pushed through Kafka to a data lake like BigTable; or request-specific metadata pulled from a service call and sent to an error tracking service like NewRelic.

I think that the single defining characteristic of tracing, then, is that it deals with information that is request-scoped. Any bit of data or metadata that can be bound to lifecycle of a single transactional object in the system. As examples: the duration of an outbound RPC to a remote service; the text of an actual SQL query sent to a database; or the correlation ID of an inbound HTTP request.

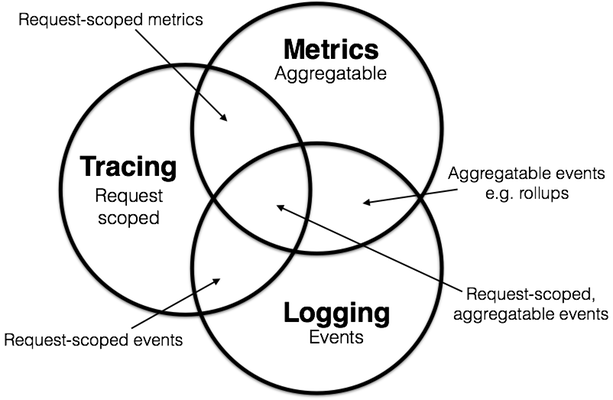

With these definitions we can label the overlapping sections.

Certainly a lot of the instrumentation typical to cloud-native applications will end up being request-scoped, and thus may make sense to talk about in a broader context of tracing. But we can now observe that not all instrumentation is bound to request lifecycles: there will be e.g. logical component diagnostic information, or process lifecycle details, that are orthogonal to any discrete request. So not all metrics or logs, for example, can be shoehorned into a tracing system—at least, not without some work. Or, we might realize that instrumenting metrics directly in our application gives us powerful benefits, like a flexible expression language that evaluates on a real-time view of our fleet; in contrast, shoehorning metrics into a logging pipeline may force us to abandon some of those advantages.

From here we can begin to categorize existing systems. Prometheus, for example, started off exclusively as a metrics system, and over time may grow towards tracing and thus into request-scoped metrics, but likely will not move too deeply into the logging space. ELK offers logging and roll-ups, placing it firmly the aggregatable events space, but seems to continuously accrue more features in the other domains, pushing it toward the center.

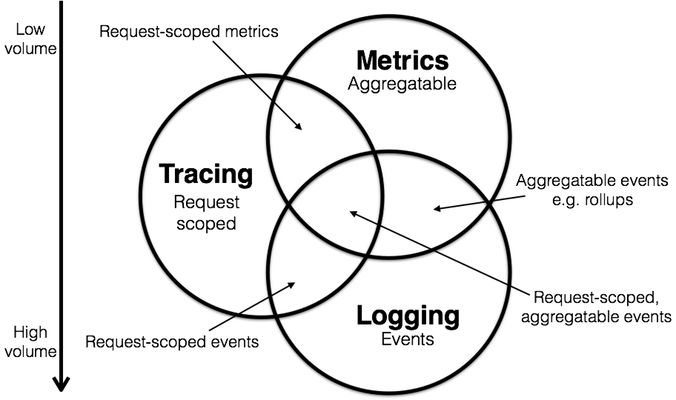

Further, I observed a curious operational detail as a side-effect of this visualization. Of the three domains, metrics tend to require the fewest resources to manage, as by their nature they “compress” pretty well. Conversely, logging tends to be overwhelming, frequently coming to surpass in volume the production traffic it reports on. (I wrote a bit more on this topic previously.) So we can draw a sort of volume or operational overhead gradient, from metrics (low) to logging (high)—and we observe that tracing probably sits somewhere in the middle.

Maybe it’s not a perfect description of the space, but my sense from the Summit attendees was that this categorization made sense: we were able to speak more productively when it was clear what we were talking about. Maybe this diagram can be useful to you, too, if you’re trying to get a handle on the product space, or clarify conversations in your own organizations.