Go for Industrial Programming

This was originally a talk at GopherCon EU 2018.

Setting some context

So I’m actually in a bit of a strange situation right now. And I think everyone who takes the stage here, or at any conference, is in the same sort of bind.

The inimitable JBD has given us the professional tip that we should never blindly apply dogmatic advice, and that we should use our judgment each and every time. Presumably also with that selfsame tip. But I have applied my judgment to this statement, and I judge it to be true.

Some guy on the internet has additionally observed that the longer it is you’re in the tech industry the more your opinions end up being well it depends and I’m not sure and that these don’t quite make for good talks. That also feels true to me—at least, if you’re doing things right. It’s my experience that if you find that you’re getting more strongly opinionated as you advance in your career, chances are you’re caught in a rut and becoming an expert beginner. Not great!

Paralysis?

Taken together, these two truths about advice-giving seem to push us into a paralysis. The more experienced I become, the less sure I am about anything, and the less likely I am to deliver actionable advice to you, the audience. And the better you are at receiving advice, the less likely you are to believe what I say. So what am I even doing up here? Should we all go home?

To break out of this paralysis I think we can employ a couple of strategies. First, we can ensure that when we give advice, we place it into the specific context where it makes sense. If we can define an explicit scope of applicability, we can carve out a little space for ourselves to have a well-defined opinion.

That’s what I’ve tried to do with the title of the talk. I’m speaking today about programming in an industrial context. By that I mean

- in a startup or corporate environment;

- within a team where engineers come and go;

- on code that outlives any single engineer; and

- serving highly mutable business requirements.

This describes my work environments for most recent memory. I suspect it does for a lot of you, too. And the best advice for Go in this context is sometimes different than for Go in personal projects, or large open-source libraries, and so on.

And to speak to JBD’s point, I should be careful to always justify the advice I give, so that you can follow the chain of reasoning yourself, and draw your own conclusions. I’ve tried my best to do that in this talk.

So with those guidelines in mind, let’s review the set of topics I’d like to try to cover. I’ve tried to select for areas that have routinely tripped up new and intermediate Gophers in organizations I’ve been a part of, and particularly those things that may have nonobvious or subtle implications.

Table of Contents

- Structuring your code and repository

- Program configuration

- The component graph

- Goroutine lifecycle management

- Observability

- Testing

- How much interface do I need?

- Context use and misuse

Structuring your code and repository

One thing I see frequently among my colleagues, especially those very new to Go, is an expectation of a rigid project structure, often decided a priori at the start of the project. I think this is generally more problematic than helpful. To understand why, remember the fourth, and maybe most important, property of industrial programming:

Industrial programming ... serves highly mutable business requirements

The only constant is change, and the only rule of business requirements is that they never converge, they only diverge, grow, and mutate. So we should make sure our code accommodates this fact of life, and not box ourselves in unnecessarily. Our repos, our abstractions, our code itself should be easy to maintain by being easy to change, easy to adapt, and, ultimately, easy to delete.

There are a few things that are generally good ideas. If your project has multiple binaries, it’s a good idea to have a cmd/ subdirectory to hold them. If your project is large and has significant non-Go code, like UI assets or sophisticated build tooling, it might be a good idea to keep your Go code isolated in a pkg/ subdirectory. If you’re going to have multiple packages, it’s probably a good idea to orient them around the business domain, rather than around accidents of implementation. That is: package user, yes; package models, no. There are a couple of good articles for package design: Ben Johnson’s Standard Package Layout and Brian Ketelsen’s GopherCon Russia talk this year had some good advice.

Of course, business domain and implementation are not always

strictly separated. For example, large web applications tend to intermingle

transport and core business concerns. Frameworks like

GoBuffalo

encourage package names like actions, assets, models, and templates.

When you know you’re dealing with HTTP exclusively, there are advantages to

going all-in on the coupling.

When you know you’re dealing with HTTP exclusively, there are advantages to

going all-in on the coupling.

Tim Hockin also suggests we align packages on dependency boundaries. That is, have separate packages for e.g. RedisStore, MySQLStore, etc. to avoid external consumers having to include and compile support for things they don’t need. In my opinion, this is an inappropriate optimization for packages with a closed set of importers, but makes a lot of sense for packages widely imported by third parties, like Kubernetes, where the size of the compilation unit can become a real bottleneck.

So there’s a spectrum of applicability. I think the best general advice is to only opt-in to a bit of structure once you feel the need, concretely. Most of my projects still start out as a few files in package main, bundled together at the root of the repo. And they stay that way until they become at least a couple thousand lines of code. Many, even most, of my projects never make it that far. One nice thing about Go is that it can feel very lightweight; I like to preserve that as long as possible.

Program configuration

I feel like I say this in almost every talk I give or article I write, but I wouldn’t want to break the streak now, so let me repeat myself: Flags are the best way to configure your program, because they’re a self-documenting way to describe the configuration surface area of your program at runtime.

This is particularly important in industrial contexts, where whoever is operating a service may not be its original author. If running your program with the -h flag provides a complete list of the knobs and switches that controls its behavior, then it’s very easy for an on-call engineer to adjust something during an incident, or for a new engineer to get it running in their dev environment. Much easier than having to hunt down a set of relevant environment variables in (probably outdated) documentation, or figure out the syntax and valid key names of a config file format.

This doesn’t mean never use env vars or config files. There are good reasons to use either or both in addition to flags. Env vars can be useful for connection strings and non-secret auth tokens, especially during dev. And config files are great for declaring verbose configs, as well as being the most secure way to get secrets into a program. (Flags can be inspected by other users of the system, and env vars can easily be set and forgotten.) Just ensure that explicit commandline flags, if given, take highest priority.

I’ve speculated in the past about a theoretical configuration allowed env vars and config files in various formats, on an package which mandated the use of flags for config, but also opt-in basis. I have strong opinions about what that package should look like, but haven’t yet spent the time to implement it. Maybe I can put this out there as a package request?

var fs myflag.FlagSet

var (

foo = fs.String("foo", "x", "foo val")

bar = fs.String("bar", "y", "bar val", myflag.JSON("bar"))

baz = fs.String("baz", "z", "baz val", myflag.JSON("baz"), myflag.Env("BAZ"))

cfg = fs.String("cfg", "", "JSON config file")

)

fs.Parse(os.Args, myflag.JSONVia("cfg"), myflag.EnvPrefix("MYAPP_"))

The component graph

Industrial programming means writing code once and maintaining it into perpetuity. Maintenance is the continuous practice of reading and refactoring. Therefore, industrial programming overwhelmingly favors reads, and on the spectrum of easy to read vs. easy to write, we should bias strongly towards the former.

Dependency injection is a powerful tool to optimize for read comprehension. And here I definitely don’t mean the dependency container approach used by facebook-go/inject or uber-go/dig, but rather the much simpler practice of enumerating dependencies as parameters to types or constructors.

Here’s an example of container-based dependency injection that recently made the rounds:

func BuildContainer() *dig.Container {

container := dig.New()

container.Provide(NewConfig)

container.Provide(ConnectDatabase)

container.Provide(NewPersonRepository)

container.Provide(NewPersonService)

container.Provide(NewServer)

return container

}

func main() {

container := BuildContainer()

if err := container.Invoke(func(server *Server) {

server.Run()

}); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

The func main is compact, and BuildContainer has the appearance of being pithy and to-the-point. But the Provide method requires reflection to interpret its arguments, and Invoke gives us no clues as to what a Server actually needs to do its job. A new employee would have to jump between multiple contexts to build a mental model of each of the dependencies, how they interact, and how they’re consumed by the server. This represents a bad tradeoff of read- vs. write-comprehension.

Compare against a slightly adapted version of the code that this example is meant to improve:

func main() {

cfg := GetConfig()

db, err := ConnectDatabase(cfg.URN)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

repo := NewPersonRepository(db)

service := NewPersonService(cfg.AccessToken, repo)

server := NewServer(cfg.ListenAddr, service)

server.Run()

}

The func main is longer, but in exchange for that length we get unambiguous explictness. Each component is constructed in dependency-order, with errors handled inline. Each constructor enumerates its dependencies as parameters, allowing new code readers to quickly and easily build a mental model of the relationship graph between components. Nothing is obscured behind layers of indirection.

If a refactor requires a component to acquire a new dependency, it simply needs to be added to the constructor. The next compile will trigger errors that precisely identify the parameter lists need to be updated, and the diff in the resulting PR will clearly show the flow of the dependency through the graph.

I claim this strictly superior to the previous method, where relationships are much harder to extract from the code as written, and much of the failure detection is deferred until runtime. And I claim it’s increasingly superior as the size of the program (and the size of the func main) grows, and the benefits of plain and explicit initialization compound.

When we talk about read comprehension, I like to reflect on what I think is the single most important property of Go, which is that it is essentially non-magical. With very few exceptions, a straight-line reading of Go code leaves no ambiguity about definitions, dependency relationships, or runtime behavior. This is great.

But there are a few ways that magic can creep in. One unfortunately very common way is through the use of global state. Package-global objects can encode state and/or behavior that is hidden from external callers. Code that calls on those globals can have surprising side effects, which subverts the reader’s ability to understand and mentally model the program.

Accordingly, and in deference to read-optimization and maintenance costs, I think the ideal Go program has little to no package global state, preferring instead to enumerate dependencies explicitly, through constructors. And since the only job of func init is to initialize package global state, I think it’s best understood as a serious red flag in almost any program. I’ve programmed this way for many years, and I’ve only grown to appreciate and advocate for the practice more strongly in that time.

- Explicit dependencies

- No package level variables

- No func init

Goroutine lifecycle management

Incorrect or overly-complex designs for starting, stopping, and inspecting goroutines is the single biggest cause of frustration faced by new and intermediate Go programmers, in my experience.

I think the problem is that goroutines are, ultimately, a very low-level building block, with few affordances for the sort of higher-order tasks that most people want to accomplish with concurrency. We say things like “never start a goroutine without knowing how it will stop,” but this advice is somewhat empty without a concrete methodology. And I think many tutorials and lots of example code, even in otherwise good references like The Go Programming Language book, do us a disservice by demonstrating concurrency concepts with leaky fire-and-forget goroutines, global state, and patterns that would fail even basic code review.

Most goroutines I see launched by my colleagues are not incidental steps of a well-defined concurrent algorithm. They tend to be structural, managing long-running things with indistinct termination semantics, often started at the beginning of a program. I think these use cases need to be served with stronger conventions.

Imagine for a moment that the orthotics of the go keyword were slightly different. What if we couldn’t launch a goroutine without also necessarily providing a function to interrupt or stop it? In effect, enforcing the convention that goroutines shouldn’t be started unless we know how they’ll be stopped.

This is what I’ve stumbled over with package run, extracted from a larger project I was working on last year. Here’s the most important method, Add:

func (g *Group) Add(execute func() error, interrupt func(error))

Add queues a goroutine to be run, but also tracks a function that will interrupt the goroutine when it needs to be killed. That enables well-defined termination semantics for the group of goroutines as a whole. For example, I use it most often when I have multiple server components that should run forever, and then Add a goroutine to trap ctrl-C and tear everything down.

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

g.Add(func() error {

c := make(chan os.Signal, 1)

signal.Notify(c, syscall.SIGINT, syscall.SIGTERM)

select {

case sig := <-c:

return fmt.Errorf("received signal %s", sig)

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

}

}, func(error) {

cancel()

})

If you’re familiar with package errgroup, this is similar at a high level, but the devil’s in the details: errgroup implicitly assumes all execute funcs will respond to the parent context provided to the group, and has no affordance to make that explicit.

There was a recent clickbaity blog post that claimed the “go statement considered harmful,” and advocated for a construct it called a nursery, of lifecycle-bound threads. Both package run and package errgroup are slightly different implementation-interpretations of this nursery concept.

Futures

So this is one form of higher-order structure. But there are plenty of others! For example, did you know Go had futures? It’s just a little bit more verbose than it might be in other languages.

future := make(chan int, 1)

go func() { future <- process() }()

result := <-future

Another way of pronouncing “future” is “async/await”.

c := make(chan int, 1)

go func() { c <- process() }() // async

v := <-c // await

Scatter-gather

We also have scatter-gather, which I use all the time, when I know precisely how many units of work I need to process.

// Scatter

c := make(chan result, 10)

for i := 0; i < cap(c); i++ {

go func() {

val, err := process()

c <- result{val, err}

}()

}

// Gather

var total int

for i := 0; i < cap(c); i++ {

res := <-c

if res.err != nil {

total += res.val

}

}

A good Go programmer will have a strong command of several of these higher-order concurrency patterns. A great Go programmer will be proactive in teaching those patterns to their colleagues.

Observability

Let’s talk about observability. But before we do that, let’s put some light on another kind of assumption about industrial programming: that we’re writing code that’s going to run on a server, serve requests to customers, and go through lifecycles, without having that service interrupted. This is different than code that’s shrink-wrapped and delivered to customers, or code that runs as batch jobs and isn’t customer facing.

I largely agree with what Charity told us earlier in the program. In particular, I agree that a core invariant of our distributed industrial systems is that there’s simply no cost-effective way to do comprehensive integration or smoke testing. Integration or test environments are largely a waste; more environments will not make things easier. For most of our systems, good observability is simply more important than good testing, because good observability enables smart organizations to focus on fast deployment and rollback, optimizing for mean time to recovery (MTTR) instead of mean time between failure (MTBF).

The question for us is: what does a properly observable system in Go look like? I guess there’s no single answer, no package I can tell you to import to solve the problem once and for all. The observability space is fractured, with many vendors competing for their particular worldview. There’s a lot to be excited about, but the dust hasn’t settled on winners yet. While we wait for that to happen, what can we do in the meantime?

If we lived in a more perfect world, it wouldn’t matter. If we

had a perfect observability data collection system, where all

interpretation could be done at query-time with zero cost, we

could emit raw observations to it, with infinite detail, and

be done with it. But what makes the field interesting, or

challenging, is of course that no such data system exists.

So we’ve had to make engineering decisions, compromises, imbuing

certain types of observations with semantic meaning, to enable

specific observability workflows.

be done with it. But what makes the field interesting, or

challenging, is of course that no such data system exists.

So we’ve had to make engineering decisions, compromises, imbuing

certain types of observations with semantic meaning, to enable

specific observability workflows.

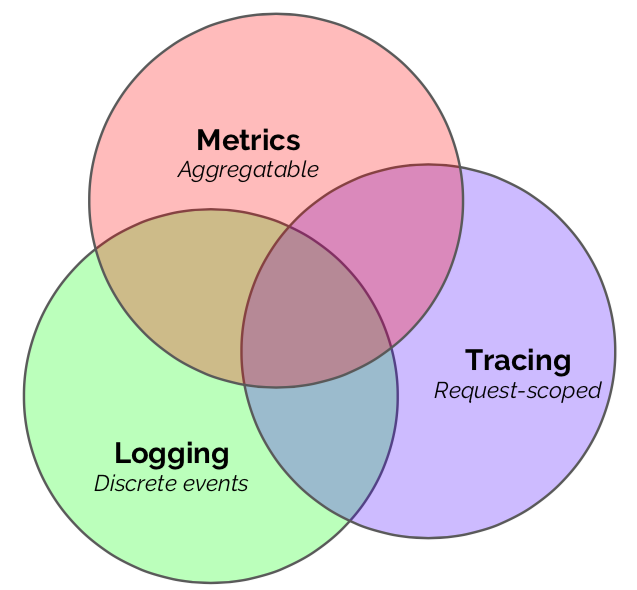

Metrics, logging, and tracing are emergent patterns of consumption of observability data, which inform the way we produce, ship, and store the corresponding signals. They’re the product of an optimization function, between how operators want to be able to introspect over their systems, and the capability of technology to meet those demands at scale. There may be other, yet-undiscovered patterns of consumption, likely driven by advances in technology, which will usher in a new era and taxonomy of observability. But this is where we’re at today, and for the foreseeable future. So let’s see how to best leverage each of them in Go.

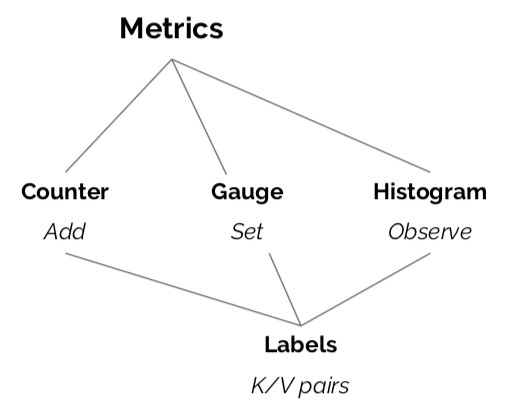

Metrics

Metrics are counters, gauges, and histograms, whose observations are statistically combined and reported to a system that allows fast, real-time exporation of aggregate system behavior. Metrics power dashboards and alerts.

Most metric systems provide Go client libraries by this point, and the standard exposition formats, like StatsD, are pretty well understood and implemented. If your organization already has institutional knowledge around a given system, standardize on it; if you’re just getting started or looking to converge on one system, Prometheus is best-in-class.

What isn’t good enough anymore are host- or check-based systems like Nagios, Icinga, or Ganglia. These keep you trapped in monitoring paradigms that stopped making sense a long time ago, and actively impede making your system observable.

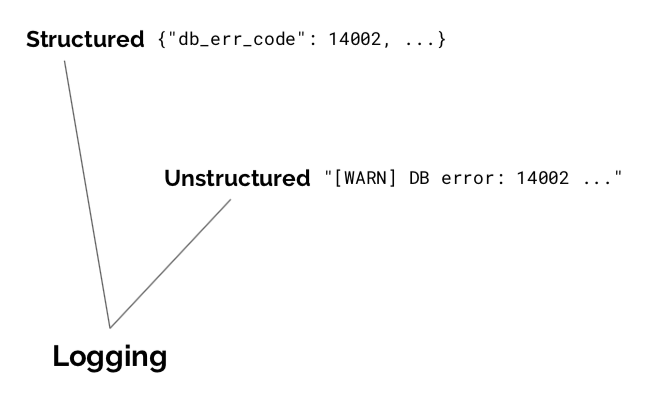

Logging

Logs are streams of discrete events reported at full fidelity to a collection system, for later analysis, reporting, and debugging. Good logs are structured and permit flexible post-hoc manipulation.

There are lots of great logging options in Go these days. Good logging libraries are oriented around a logger interface, rather than a concrete logger object. They treat loggers as dependencies, avoiding package global state. And they enforce structured logging at callsites.

Logs are abstract streams, not concrete files, so avoid loggers that write or rotate files on disk; that’s the responsibility of another process, or your orchestration platform. And logging can quickly dominate runtime costs of a system, so be careful and judicious in how you produce and emit logs. Capture everything relevant in the request path, but do so thoughtfully, using patterns like decorators or middlewares.

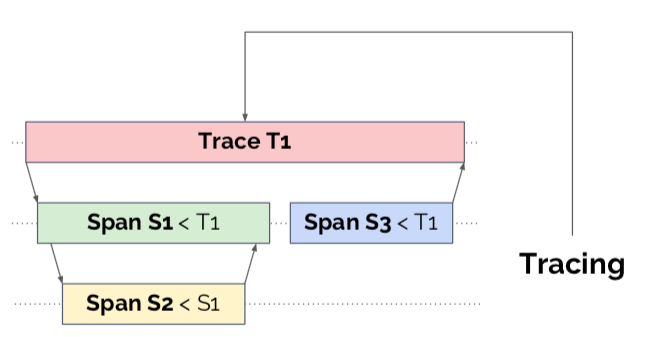

Tracing

Tracing deals with all request-scoped performance data, especially as that data crosses process and system boundaries in a distributed system. Tracing systems organize metadata into tree structures, enabling deep-dive triage sessions into specific anomalies or events.

Tracing implementations these days are centered around OpenTracing, a client-side API standard implemented by concrete systems like Zipkin, Jaeger, Datadog, and others. There’s also interesting work being done in OpenCensus, which promises a more integrated environment.

Tracing needs to be comprehensive if it’s going to be useful, and of all of the pillars of observability it has the strictest set of domain objects and verbs. For those reasons the costs of properly implementing tracing are very high, and may only make sense to start working on when your distributed system is quite large, perhaps beyond several dozen microservices.

Each pillar of observability has different strengths and weaknesses. I think we can compare them along different axes: CapEx, the initial cost to start instrumenting and collecting the signals; OpEx, the ongoing cost to run the supporting infrastructure; Reaction, how good the system is at detecting and alerting on incidents; and Investigation, how much the system can help to triage and debug incidents. My subjective opinions follow:

| Metrics | Logging | Tracing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CapEx | Medium | Low | High |

| OpEx | Low | High | Medium |

| Reaction | High | Medium | Low |

| Investigation | Low | Medium | High |

In terms of CapEx, logging systems are the easiest to get started, and adding log instrumentation to your code is easier and more intuitive than the alternatives. Metrics are a bit more involved, but most metrics collection systems are still relatively self-contained and pretty easy to deploy. Tracing, in contrast, is time-intensive to install across your fleet, and the tracing collection systems are typically large and require some specialized database knowledge.

In terms of OpEx, it’s my experience that keeping a logging system online takes disproportionate effort, often being just as hard or harder than the corresponding production systems—made more difficult by the tendency for most organizations to indiscriminately over-log. Tracing systems benefit from the upfront costs and generally get on OK with aggressive ingest sampling and regular database maintenance. Metrics systems, in contrast, benefit from the natural data compression that occurs from statistical aggregation, and have generally very low maintenance costs. Of course, if you choose to use a vendor, these costs translate pretty directly into dollars.

In terms of reactive capability, metrics systems are explicitly designed to serve dashboard and alert use cases, and excel here. Logging systems frequently have tooling to perform aggregates or roll-ups that can drive dashboards and alerts, with a bit of work. And tracing systems generally don’t have an ability to define, detect, or signal on anomalies.

When it comes to investigation, however, the tables are turned. Metric systems lose data fidelity by design, and usually provide no good way to dig into the root cause of a problem after it’s detected. Logging systems do much better, especially if you do structured logging and a logging system with a rich query language. And tracing is essentially designed for deep dives on specific requests or request-classes, sometimes being the only way to identify complex maladaptive behaviors.

The lesson here is that no single observability paradigm will solve all of your observability needs; they’re all part of a complete observability breakfast. From their unique characteristics I think we can derive some general advice:

- First, invest in basic, comprehensive metrics, to power a uniform set of dashboards and alerts for your components. In practice, this is often enough insight to detect and solve a huge class of problems.

- Next, invest in deep, high-cardinality, structured logging, for incident triage and debugging of more complex issues.

- Finally, once you're at a large-enough scale and have well-defined production readiness standards, investigate distributed tracing.

Testing

Although observability probably trumps integration testing for large distributed systems, unit and limited integration testing is still fundamental and necessary for any software project. In industrial contexts especially, I think its greatest value is providing a sort of sanity-check layer to new maintainers that their changes have the intended scope and effect.

It follows that tests should optimize for ease-of-use. If an entry-level developer can’t figure out how to run your project’s tests immediately after cloning the repo, there is a serious problem. In Go, I think this means that running plain go test in your project with no additional set-up work should always succeed without incident. That is, most tests should not require any sort of test environment, running database, etc. to function properly and return success. Those tests that do are integration tests, and they should be opt-in via test flag or environment variable:

func TestComplex(t *testing.T) {

urn := os.Getenv("TEST_DB_URN")

if urn == "" {

t.Skip("set TEST_DB_URN to run this test")

}

db, _ := connect(urn)

// ...

}

The testing pyramid is good general advice, and suggests that you should focus most of your efforts on unit testing. In my experience, the ideal ratios are even more extreme than the pyramid suggests: if you have good production observability, as much as 80–90% of your testing effort should be focused toward unit tests. In Go, we know that good unit tests are table-driven, and leverage the fact that your components accept interfaces and return structs to provide fake or mock implementations of dependencies, and test only the thing being tested.

I like to reference this talk as frequently as possible: Mitchell Hashimoto’s Advanced Testing with Go from last year’s GopherCon is probably the single best source of information about good Go program design in industrial contexts I’ve seen to date. If your team writes Go, it’s essential background material.

There’s not much more to say on the subject. The relative stability of testing best practices over time is a welcome reprieve. As before and as always: gunning for 100% test coverage is almost certainly counterproductive, but 50% seems like a good low watermark; and avoid introducing testing DSLs or “helper packages” unless and until your team gets explicit, concrete value from them.

How much interface do I need?

When we talk about testing, we talk about mocking dependencies via interfaces, but we often don’t really describe how that works in practice. I think it’s important to observe that the Go type system is not nominal, but rather it is structural. Looking at interfaces as a way to classify implementations is the wrong approach; instead, look at interfaces as a way to identify code that expects common sets of behaviors. Said another way, interfaces are consumer contracts, not producer (implementor) contracts—so, as a rule, we should be defining them at callsites in consuming code, rather than in the packages that provide implementations.

How much interface do you need? Well, there’s a spectrum. As much as makes sense at your callsites, especially with the aim to help testing. At one extreme, we could model every dependency to every function with a tightly-scoped interface definition. In limited circumstances this may make sense! For example, if your components are coarse-grained, well-established, and unlikely to change in the future.

But especially in industrial contexts, it’s more likely that you’ll have a mix of abstractions, which are fluctuating over time. In this case, you’ll probably want to try to define interfaces at “fault lines” in your design. Two natural boundary points are between func main and the rest of your code, and along package APIs. Defining dependency interfaces there is a great place to start, as well as a great place to start thinking about defining unit tests.

Context use and misuse

Go 1.7 brought us package context, and since then, it’s been steadily infecting our code. This isn’t a bad thing! Contexts are a well-understood and ubiquitous way to manage goroutine lifecycles, which is a big and hard problem. In my experience this is their most important function. If you have a component that blocks for any reasons—typically network I/O, sometimes disk I/O, maybe due to user callbacks, and so on—then it should probably take a context as its first parameter.

The pattern is so ubiquitous, I’ve started to design this into my server types and interfaces from the beginning. Here’s an example from a recent project that connected to Google Cloud Storage:

// reportStore is a thin domain abstraction over GCS.

type reportStore interface {

listTimes(ctx context.Context, from time.Time, n int) ([]time.Time, error)

writeFile(ctx context.Context, ts time.Time, name string, r io.Reader) error

serveFile(ctx context.Context, ts time.Time, name string, w io.Writer) error

}

Writing components to be context-aware for lifecycle semantics is straightforward: just make sure your code responds to ctx.Done. Using the value propagation features of contexts has proven to be a bit trickier. The problem with context.Value is that the key and value are untyped and not guaranteed to exist, which opens your program up to runtime costs and failure modes that may otherwise be avoidable. My experience has been that developers over-use context.Value for things that really ought to be regular dependencies or function parameters.

So, one essential of thumb: only use context.Value for data that can’t be passed through your program in any other way. In practice, this means only using context.Value for request-scoped information, like request IDs, user authentication tokens, and so on—information that only gets created with or during a request. If the information is available when the program starts, like a database handle or logger, then it shouldn’t be passed through the context.

Again, the rationale for this advice boils down to maintainability. It’s much better if a component enumerates its requirements in the form of a constructor or function parameter, checkable at compile time, than if it extracts information from an untyped, opaque bag of values, checkable only at runtime. Not only is the latter more fragile, it makes understanding and adapting code more difficult.

In summary

I’ve been doing this best practice series for six years now, and while a few tips have come and gone, especially in response to emerging idioms and patterns, what’s remarkable is really how little the foundational knowledge required to be an effective Go programmer has changed in that time. By and large, we aren’t chasing design trends. We have a language and ecosystem that’s been remarkably stable, and I’m sure I don’t just speak for myself when I say I really appreciate that.

I think it’s great to orient ourselves among each other at conferences like this one. But I think the best thing we can do here is build empathy for each other. If we do our job right, as the number of Go programmers continues to grow, the community will become increasingly diverse, with different workflows, contexts, and goals. I’m happy to have presented some experience reports from my own journey with Go, and I’m excited to hear and understand all of yours. Thanks a bunch!

🏌️♂️